Conditions

The following levels are key for political conditions:

- At the global level, it’s about a globally level playing field.

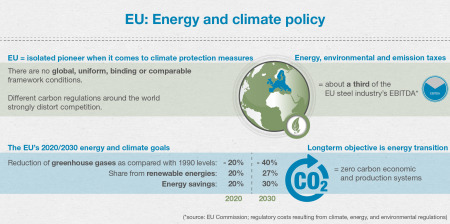

- At the European level, it’s about how and at what price the EU will achieve its energy and climate goals for 2030 and beyond (see box). Specifically, it’s about lowering carbon emissions by saving energy and migrating to renewable energies.

- For the voestalpine Group, the European perspective is the most important because the most energy and carbon intensive sites are concentrated in Europe.

Following the 2015 World Climate Summit in Paris, a first step has been taken to achieve a globally level playing field. For voestalpine, the key questions in the medium term will still be decided at the national and above all EU level (energy union/energy transition, reform of the Emissions Trading System, transformation, …). It remains open whether the EU will see the result of the Climate Summit as a reason to again tighten the legal climate targets or whether it will wait to see to what extent other regions actually take part in global climate protection.

New technologies for climate protection

Impact of EU climate policy on voestalpine

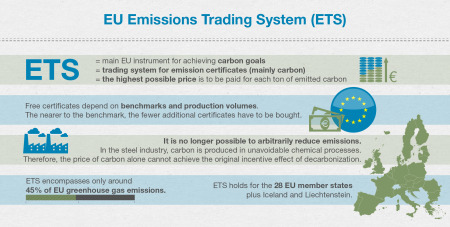

Currently, the EU’s most important instrument is the Emissions Trading System (ETS). The ETS is a trading system for emission certificates, mainly for carbon dioxide (carbon). It is primarily aimed at setting the highest possible price for each ton of carbon emissions. The distribution of free certificates takes place based on EU-wide “benchmarks” and on a company’s production quantity in certain reference periods. The nearer a plant comes to the benchmark, the fewer additional certificates it has to buy. The problem with the system is that it is not possible to continue to reduce emissions further with today’s technologies, especially not in the steel industry where carbon is produced in unavoidable chemical processes. The price of carbon alone cannot achieve the original incentive effect of decarbonization.

Another problem with the ETS is that it creates injustices between individual sectors and within a sector. Of all European steel companies, voestalpine achieves the best carbon values, but it is still the only net payer in the ETS. The reasons for this are:

- The distribution of free certificates is based on historical production data before 2009 => due to increased production in the past few years, voestalpine has considerable cost disadvantages whereas other companies receive free certificates due to post-crisis declining production.

- Even the best plants cannot reach the benchmark (theoretical best value) for free certificates, and plans are to decrease it further.

voestalpine position

For voestalpine, the current conditions present a great challenge, especially since there are still many open questions: What does Europe’s future climate and energy policy look like? Where will the carbon price end up? Which technologies can replace existing processes in the long term? Therefore, framework conditions that provide long-term planning and legal security as well as the coordinated efforts of politicians, the energy sector, and industry are decisive for voestalpine:

- Achieving a globally level playing field for energy and climate policy

- Fast implementation of the EU “energy union” (framework strategy for climate, energy and growth policy topics)

- Instead of the highest possible carbon prices, what is needed is capital to develop new technologies for climate protection.

- 100% free certificates for the “best” companies based on real production, updated and realistic benchmarks—without a bias introduced by correction factors.

- Protecting exposed industries from carbon leakage (“shifting” production, workplace and carbon to other regions)

Concentrating on carbon emissions and making them as expensive as possible to achieve the climate goal is not enough. It is more a question of energy and how it is produced—it must come from renewable sources and be available in sufficient quantities at a competitive price.

Less carbon = less energy? Wrong!

Why “energy and climate”? Because less carbon in steel production does not mean less energy—on the contrary. An example: today at its major steel locations, voestalpine is “energy self-sufficient”, i.e. it meets its own electricity needs through expensive fossil fuel recovery (coal/coke). Were a zero-carbon economy one day to become reality, the needed renewable energy would have to come from an external network. In the case of voestalpine, this is equivalent to more than 30 large hydraulic power plants The “energy question” is therefore the deciding factor for this process, not purely focusing on the highest possible carbon price.